Pirro

1999 | Tirana, Albania | Age: 12

In order to understand who I am, we must go back a long time. The reason I want to talk has less to do with me and much more to do with my parents. Their approach has always been to defend us against every single thing that could possibly happen. They were from very different lives, growing up in a communist Albania. This wasn’t lighthearted communism. Albania and the USSR were brethren at the time, and when the USSR became too liberal in the early 60s, we severed ties and aligned ourselves with Maoist China, as the true champion of proper Marxism, Leninism, and communism. This is the background against which everything happened.

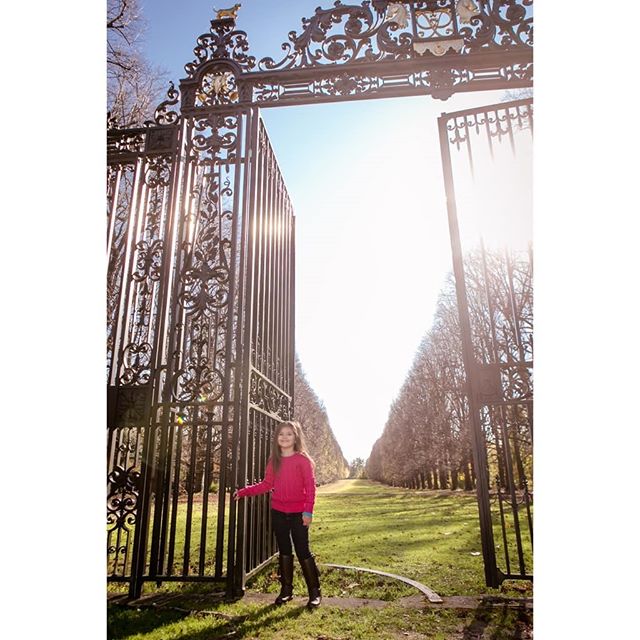

My parents became engineers because in communist countries these hard skills were much more sought after than the softer skills, like the arts and athletics. My father had played soccer professionally, but because of societal pressures and his parents, he quit at 22 to become an engineer. By giving me his pin, I thought he was continuing his dream, but it wasn’t entirely true. Though my father had disagreed with his own father when he was forced to quit soccer, he had done the same thing to me. I wanted to play so badly! My dad didn’t think I was good enough, but he asked his friend to let me attend a practice with his youth club. My mom bought me a red shirt and black shorts to blend in with the rest of the kids. I did fine at practice, but during scrimmage this gypsy kid - excuse me, member of the Roma community - and I went for the ball, knocked heads, and landed on the ground. We both got up at the same time. He went for the ball and kept playing. My response was, “Let me clean up myself because mom is going to yell at me for having dirty clothes.” At that point my dad said, “This is not for you. Stay home. Be the math guy with the clean clothes.”

When we came here I continued playing. I still play now in the New York Cosmopolitan Soccer League. I don’t think my dad was disappointed that I didn’t go into soccer professionally. He had actually made a serious effort never to approve of it. My mom and my sisters came to all my high school games; he did not. While he was fine with it as a hobby, he never encouraged me to pursue it professionally because he didn’t want me to waste my time. He realized early, and rightfully so, that my strength was in the analytical, academic world. He is so practical that he never chose a path with a bigger reward but small odds. If my dad knew that I enjoy doing stand-up comedy now and then, he would think it such a waste! Too much in the arts world, too risky.

My mom had also been very sporty and had played basketball and volleyball. But in the 1970s, women couldn’t play sports professionally, and it wasn’t prestigious to have a daughter who was just a volleyball player. So she went into civil engineering. In fact, she became so amazing at it that she received the only scholarship in the university to study post bacc in Florence in the early 1990s.

My parents worked in Italy for 2 or 3 years, while I stayed with my grandparents in Albania. They came back to Albania with substantial savings because the Italian lira had so much more value than the Albanian lek. My dad started a construction company and made pretty good money. We came to America via the green card lottery with the clothes on our backs and $30,000!

In the 90s the newly established democratic freedom paved the way for ponzi schemes because of the cash shortage and a financial liquidity problem. In 1997 all of these schemes collapsed, and people lost all their savings. Because my mom had been so scared of this easy money, my dad had not invested much, and we didn’t lose much. Wealthwise, we were in the top 10% of the country, but the 10% above us were totally corrupt. Needless to say, we were comfortable. In 1997 when all this happened, people became very angry. Mobs descended upon the arsenal depot, and the entire country became weaponized. The AK47 would sell for as cheap as $100. My parents had a constructive debate about whether to keep weapons at home. On the one hand they had 3 little kids to protect. On the other hand they were afraid that we’d find the guns and kill each other. We ended up not having weapons. We lived on the 5th floor, and the thugs with the AK47s would start shooting in the air for fun. Sometimes the bullets would go into the 5th floor apartments. When we’d hear them start shooting, we’d hide under the bed, not that it could protect us much. So even though we had money, this was our reality. Luckily for us, we got the green card, and we came here with money. This isn’t a story of scrappy immigrants that you often hear.

In Albania, sometimes we would catch a satellite signal from Italy and watch Italian broadcasts of movies like Home Alone 2: Lost in New York, where the wealthy guy had a McMansion, and Trump was a good thing at the time. There were the skyscrapers, Central Park, Carnegie Hall. We had this perception of the New York glamor. There were no movies about Queens. Coming to America wasn’t as popular on Italian television. When the cab driver picked us up from the airport, he took us on the worst possible route. We saw the most demoralizing, the most obscene ghetto parts imaginable. There was dirty snow and garbage everywhere. I started crying. My mom became emotional about our new reality. We had left a fairly comfortable life for Atlanic fucking Avenue! They didn’t realize just how difficult it would be.

Many immigrants stay in blue collar jobs, but not my parents. After 2 months of working at the post office, my mom joined an architecture firm. A few years later, she became a math teacher and has been ever since. Within a year my dad became a land surveyor, which is exactly what he had been doing in Albania, so he knew all the trigonometry used to make measurements. They landed on their feet here and have done quite well. They put 3 kids through school, and because of that, I was able to save enough money for my own apartment. To buy my own place in the city at 25 was massive. My parents were super proud and supportive.

My sisters and I had been completely shielded from everything. My parents did not come home and say, “I’m so tired” or “It’s so soul-draining to have these menial jobs.” Nothing like that. Because they’ve worked so hard, I always have to try harder than everyone else because my bar for success is set higher. That’s why I was never quite satisfied unless I did something substantial. I wasn’t happy living in the city unless I owned my place. I had to try harder because my parents gave us everything. Here’s how I see it: I’m the quarterback who gets the glory, and they are the linebackers blocking everything that gets in my way. “Wow Brady, what a game!” But look, he did nothing! The coach told him to run a certain play, and he did it. The linebackers are the unsung heroes. And my parents know it too, that’s why a 95% was never good enough, and that is why I started my own venture with Class and Co. It wasn't enough to have a regular job. In my own way I applied my dad's entrepreneurial spirit and affinity for measured risk, my mom's ethical approach, and their combined academic angle. Like Albania itself, I am of their two worlds.

My dad gave me this bottle of brandy when I bought my apartment. Some time ago he had hurt his elbow in a fall at work. He never complained. I would ask him how he was, and he would waive me off, telling me that I should always make guests welcome. That’s the way they are. My parents don’t care about themselves as long as the kids are doing ok. We are their wealth. Their fortunes rise and fall with me and my sisters. So he had to make sure that I would always have brandy to offer guests. And it had to be Albanian brandy. Albania was the place where two worlds always met - the Byzantine Empire and the Roman Empire; the Ottoman Empire and Christian Europe; Western Europe and communism. We were always in the middle of two opposing forces, much like my parents - all sports and all analytics. Albania may not have the richest culture because we have been conquered and diluted so many times, but we hold on very tightly to the few things we do have.